New Zealand in Sunlight – Photo from NASA

Poetry Lab piece by Julianne Warren

Introduction

Studying birds helped me earn a Ph.D. in conservation biology. I’ve also written an intellectual biography of the twentieth-century American ecologist and author of A Sand County Almanac, Aldo Leopold. My book, Aldo Leopold’s Odyssey, unfolds his work progressing toward the idea of land health—an ethically right and sensible effort to learn life ways complementing “the capacity of the land for self-renewal.” Moving forward, Leopold saw, would require divorcing the data-gleaning process of science from the standard of power and re-marrying it to a humanity characterized by affection, wonder, and respect for nature. Such qualities, Leopold understood, “step beyond ‘science’ in the narrow sense, because everything really important steps beyond it.”

Studying birds helped me earn a Ph.D. in conservation biology. I’ve also written an intellectual biography of the twentieth-century American ecologist and author of A Sand County Almanac, Aldo Leopold. My book, Aldo Leopold’s Odyssey, unfolds his work progressing toward the idea of land health—an ethically right and sensible effort to learn life ways complementing “the capacity of the land for self-renewal.” Moving forward, Leopold saw, would require divorcing the data-gleaning process of science from the standard of power and re-marrying it to a humanity characterized by affection, wonder, and respect for nature. Such qualities, Leopold understood, “step beyond ‘science’ in the narrow sense, because everything really important steps beyond it.”

It was something “really important” that I was pursuing as I listened to birdsongs catalogued in the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology’s Macaulay Library. I was listening for recordings I could use to accompany an invited talk honoring another American naturalist and writer, one whom Leopold also admired, the nineteenth century’s John Burroughs. In my address, I wanted to explore hope, the meaning of which seemed at a vulnerable juncture as scientific evidence increasingly pointed to humans’ failures to advance land health around the world compromising the whole of Earth health.

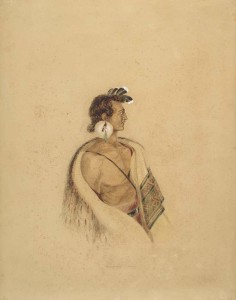

As I investigated Macaulay’s holdings, I happened upon the soundtrack of an ivory-billed woodpecker. This bird of the southeastern U.S. and Cuba is likely recently extinct. I caught my breath when I heard this vanishing voice. My awareness roused, I turned, then, to another database—the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s “Red List of Threatened Species.” Cross-listing this information with the Macaulay Library holdings, I discovered the five birds I mention below, each of whom is listed as officially extinct and also has at least one aural file archived in Cornell’s library. Each of the voices moved me.The huia (Heteralocha acutirostris) soundtrack is distinctly complex, however. As you read on, you will be invited to listen to it as well. This music, in particular, haunts me.

huia feeding together in the forest. This is the recording—a soundtrack of the sacred voices of extinct birds echoing in that of a dead man echoing out of a machine echoing through the world of today—that has become my phantom companion, and whom you may hear as you read on below.

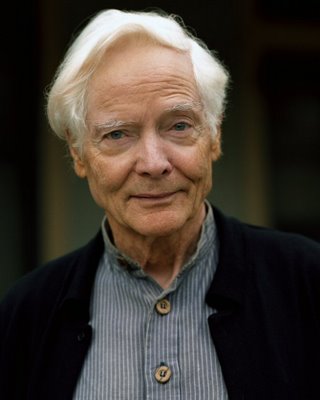

What might learning extinct birdsong—the echoes of dead language—possibly have to teach us about hope? As W.S. Merwin’s poetry helps us to grasp, we must “Learn first to listen.”

Hopes Echo

by Julianne Warren

Hope? Aching, as you are, too, from personal losses—as of my family home built in a rattling river town with planks of Hemlock forest cut down with its first people and mountain lions, then its hills overgrazed, its overgrown oldfields’ milkweeds hung with gilded pale-green chrysalises and fall’s dispersal of downy airborne seeds with burnt orange-black butterflies, all gone—the family home, soil’s health, the whole river town (but not its ghosts)—hurried by Hurricane Irene downriver into the reservoir that suckles glistening urban downstate.

Hope? Faced with global deforestation and depleted soils, climate-changed drought shrinking lakes, intensifying hurricanes, melting ice, flooding and soured seas, more wars, drowned immigrants fled from burned cities, accelerating extinctions of lives and of kinds of life, with languages lost, and with our responsibilities for these now unfolding realities.

Hope? In what? For what?

Hope mixes two abstract dimensions—desire and expectation. Expectation implies trust or confidence in someone or something. There are as many possible forms of hope, therefore, as there are combinations of diverse wants and faiths, each of which may be deemed more or less reasonable, more or less worthy. Not all hopes, that is, are of equal quality.

Even those speaking altogether against hope seem unable to escape it. Writing in Orion, for instance, Derrick Jensen tries but fails. “Hope,” he claims, “is, in fact, a curse, a bane.” He argues that hope disempowers, that people use it as an excuse to act like victims who must leave their cares in uncaring hands. And so, he says, we must move beyond hope, leave it behind. Yet Jensen can’t banish desire—his own, to protect Earth’s life, the salmon, trees, and salamanders. And, while dismissing the “magical assistance” of God, Technology, and Earth as unworthy of confidence, he calls for faith in “the really alive-you” who will act even when the task seems impossible, doing “whatever it takes.” What might be the source of this courageous, loving life energy is unsaid.

In older times hope commonly carried a more solid meaning as a fruiting place of safety relative to surrounding “wastes” of inhospitable marshy ground, craggy mountains, desert or ocean. Hope meant a haven, mating human trust and want in a fecund nesting place, within a self-renewing interdependency of soils, plants, other animals, fresh water, and an atmosphere just right to breathe and to regulate the sun’s heat.

In the nineteenth century, American poet Emily Dickinson imaginatively embodied hope, giving the haven wings and perching it within “the soul” of human beings. Since then, for many English speakers, “hope” may conjure a ceaselessly singing “thing with feathers,” unabashedly keeping people warm, from the inside, through windy storms:

I’ve heard it in the chillest land,

And on the strangest sea;

Yet, never, in extremity,

It asked a crumb of me.

“Never,” the poet of a past century says.

Yet, today, Earth’s extremities

are more extreme.

And, consequently, real birds

are dead and dying.

The current extinction rate for birds, according to accumulating scientific evidence, may be faster than any recorded across the one-hundred-and-fifty million of years of avian evolutionary history, heading toward a massive magnitude of lost forms of world-wide life. Within as few as three centuries, Earth could lose over seventy-five percent of bird species, along with a similar proportion of other kinds of creatures and hosts of plants with their distinct soil types. Not only is the quickness of loss unprecedented, so is its cause: the activities of the largest human population our planet has ever held.

Some have named this a time of human global domination, calling it the “Anthropocene.” But not all people are equally to blame for destruction. Liability falls primarily to those in power shortsightedly,simple-mindedly, and violently co-opting “resources” of Earth for their direct use–that is, largely for their marketable and consumable creations–and trading species from place to place, bringing predators, pathogens and pollution to naïve birds, directly killing them with weapons, and—by burning fossil hydrocarbons hidden in bedrock into air—changing global atmosphere and climate, further interrupting ecological interrelationships. The net consequence is the reversal of billions-of-years-old trends that augment diversity and complexity of life, out of which our own kind emerged, intertwined.

To the degree that dangers engulf earthly hopes—defined as in the physical sense of fresh-watered, fruiting islands of sheltering health—all human beings are at risk. And yet, ironically, it is human activities that are killing beings and endangering harbors of life–of communities of trees, soils, welling springs, and birds—in widening rings.

Following human contact, first Earth’s smaller islands, surrounded by the “strangest seas,” had the highest rates and numbers of bird extinctions. More recently, losses have accelerated inland on continents, encroaching even on “hot spots” where survivors still persist in shrunken refuges amid vast wastes of eroding soil, mine tailings, and parking lots. Many birds are in trouble—from ocean atoll to desert lake and mountain glen—to the whole life-entangled planet, a global island embedded within an ancient universe, as far as we know, of shimmering, though speechless, uninhabitable space.

Here is a second irony. The unwanted consequences of humans compromising Earth may awaken us to the planet’s encircling nature as our greatest hope. While our soul’s desire for a flourishing world-of-life is darkened with extinctions, our faith in life’s mysterious origins deepens. On and on the warm things with feathers sing, perched inside us.

Either way—tracking interpenetrating hopes from inside out or outside in—even if we try, we cannot kill them and keep living. But what qualities of hope are fitting in a time of such great losses? With so many individuals and forms already gone behind and ahead of us, on what can we rely or not, and to whom or what shall our desires reach?

There is a form of hope that needs chastening—one that trusts foremost in human power and, denigrating other kinds of life upon which we depend, supremely wants our own kind’s good. I feel the knotty shame in the pretense that we have not been pretending to be god, now that so many kinds of lives—and ours linked with them—are ending. I feel it acutely in W.S. Merwin’s message “For a Coming Extinction.”

There is a form of hope that needs chastening—one that trusts foremost in human power and, denigrating other kinds of life upon which we depend, supremely wants our own kind’s good. I feel the knotty shame in the pretense that we have not been pretending to be god, now that so many kinds of lives—and ours linked with them—are ending. I feel it acutely in W.S. Merwin’s message “For a Coming Extinction.”

For a Coming Extinction

Gray whale

Now that we are sending you to The End

That great god

Tell him

That we who follow you invented forgiveness

And forgive nothing

I write as though you could understand

And I could say it

One must always pretend something

Among the dying

When you have left the seas nodding on their stalks

Empty of you

Tell him that we were made

On another day

The bewilderment will diminish like an echo

Winding along your inner mountains

Unheard by us

And find its way out

Leaving behind it the future

Dead

And ours

When you will not see again

The whale calves trying the light

Consider what you will find in the black garden

And its court

The sea cows the Great Auks the gorillas

The irreplaceable hosts ranged countless

And foreordaining as stars

Our sacrifices

Join your word to theirs

Tell him

That it is we who are important

“That it is we who are important” echoes in my head, resonant with the cries of proud Narcissus. “Am I the favor-seeker or the favor sought?” the beautiful boy asks while gazing at his own reflection in a glossy, tree-shaded lake. He wets his face and hands, trying to kiss the likeness of his own lips and stroke his own cheek. The rippling hopelessness of hope so flattened into one dimension mirrors his self-destructive desperation. Unable to escape himself, Narcissus beats himself into the ground while his ardent admirer, Echo, whom he had teased and spurned, looks on, neither able to rescue him nor escape her own mad desire.

Echo thus became twice cursed herself. Earlier, jealous Juno had hobbled this voluble nymph’s voice as punishment for intruding into her affairs. Echo had been made unable to speak her own phrases, but could only mimic the last parts of what others said. “Is anyone here!” shouted Narcissus. “Here!” called Echo in reply. “Be with me, come!” cried Narcissus. Echo’s answer followed, “Come!” She tried to throw her arms around his neck, but Narcissus pushed her away. Mortified by his rejection, Echo’s body had wasted away and then her bones had fossilized, leaving her, finally, as only a voice, a wraith mourning faith feeling what is hard as stone, though rich with longing.

“Farewell!” was the last word Narcissus cried out to himself before he died, blooming later from the ground into a yellow-hearted flower. Despite her aching memory of him, Echo replied unfalteringly. Her “Farewell!”carried over the water, quieted, before moving on, the “elusive wanderer,” writes Merwin,

To Echo

What could they know of you

to be so sure of

that it frightened them

into passing judgment upon you

later from a distance

elusive wanderer speaking

when sound carries

over a river

or across a lake

recognized without being seen

beauty too far

beyond the human

then where did you go

do you go

to answer

often with voices

that once spoke for

the listeners

though only the last things

they called

ends of names greetings

the question Who

Call “greetings” to ghosts: The huia’s is one of just a handful of avian voices, so far, gone officially extinct, with remains including not only written descriptions but also archived sound recordings . You can replay the tones of the Guatemalan grebe (Podilymbus gigas), a flycatcher of Guam (Myiagra freycineti), and two birds of Hawaii—a thrush (Myadestes myadestinus) and an O’o (Moho Braccatus). The huia’s track (Heteralocha acutirostris) is more haunting yet, as you hear it echoing not only from a machine. At the request of Pakeha collector R.A.L. Bately, the dead birdsong echoes also in the whistled memory—sacred—of an old Māori man, now also un-living. Henare Hamana, the mimic, had learned the song in his youth from lingering birds on the eve of their extinction.

Call “the question Who,” writes Merwin: When I first heard this recording it caught me by surprise, and then, unabashed, looping and re-looping, as I listened, repeatedly, it became part of me, it started playing me. Perhaps if you listen now, the music also will start playing you. The voice of the huia has been taken to sound like, “Who are you?” In Māori, “Huihui!” which, in English means “assemble.” If not gods nor Earth’s ultimate treasures, who are we? Who am I? And, if hope is inescapable, what if anything or anyone, inside or out, behind or ahead is worthy of belief or right and reasonable to desire?

Time is irreversible. The past we have made cannot be undone. We may ache remembering those many who are gone. At the same time, we are faced with unfolding massive anthropogenic de-creation—to which humanity’s own future is tied. But this is not yet guaranteed. There is still time for generative transformations of hopes with, if not forgiveness, corresponding action.

Grief along with looming, unprecedented dangers caused by humans in power have shaken some of us into awareness of our loneliness, into humility, and renewed love with its resolute courage. We desire flourishing for the remains of Earth’s life. What we hear in the firmament of feathered echoes singing may enchant our trust.

I have become both carried away by and a carrier of “Huia Echoes”, an extinct bird-man-remembered song saved in a machine for passing on. Again taking Merwin’s words to heart, I am “Learning a Dead Language.” I want to leave delusions of mastery unrequited to “Learn first to listen” for the secrets the dead might impart, for the passion hidden beyond words, for what is waiting in absences. Learning to be still and receptive in various soundscapes is an ongoing project helping save my better self while connecting me intimately with others, whom I encourage likewise to cultivate an awareness of hearing, and the worthiest of hopes.

Learning a Dead Language

There is nothing for you to say. You must

Learn first to listen. Because it is dead

It will not come to you of itself, nor would you

Of yourself master it. You must therefore

Learn to be still when it is imparted,

And, though you may not yet understand, to remember.

What you remember is saved. To understand

The least thing fully you would have to perceive

The whole grammar in all its accidence

And all its system, in the perfect singleness

Of intention it has because it is dead.

You can learn only a part at a time.

What you are given to remember

Has been saved before you from death’s dullness by

Remembering. The unique intention

Of a language whose speech has died is order,

Incomplete only where someone has forgotten.

You will find that the order helps you to remember.

What you come to remember becomes yourself.

Learning will be to cultivate the awareness

Of that governing order, now pure of the passions

It composed; till, seeking it in itself,

You may find at last the passion that composed it,

Hear it both in its speech and in yourself.

What you remember saves you. To remember

Is not to rehearse, but to hear what never

Has fallen silent. So your learning is,

From the dead, order, and what sense of yourself

Is memorable, what passion may be heard

When there is nothing for you to say.

With special thanks to:

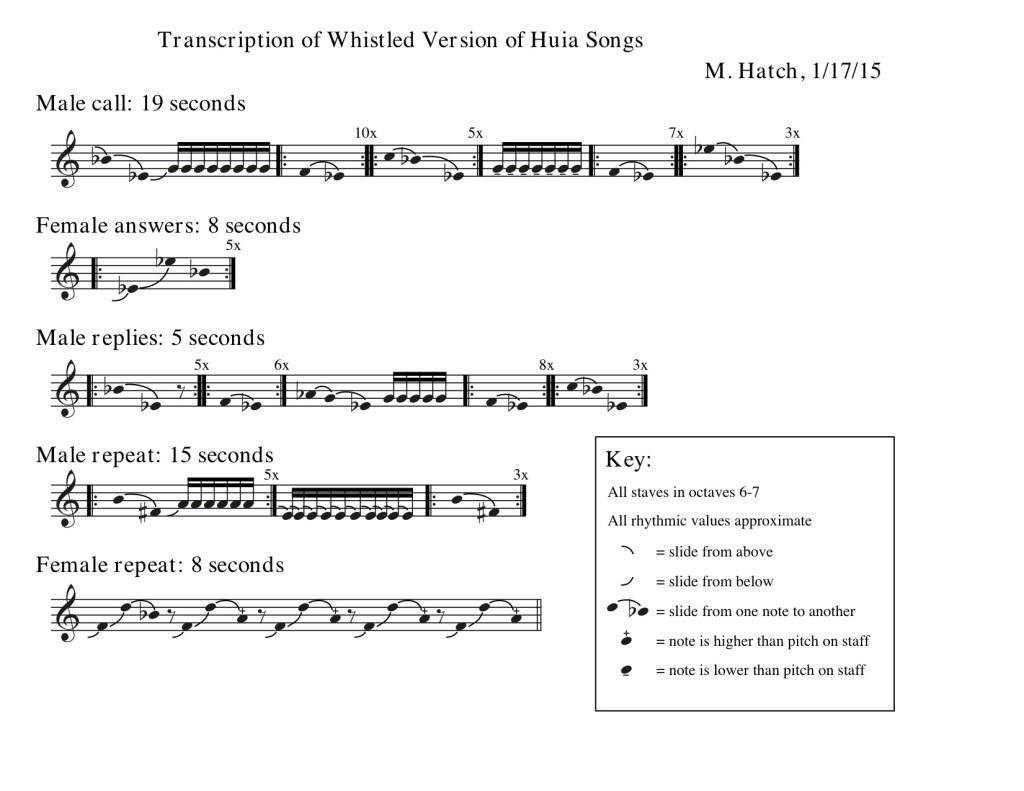

Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, USA for permission to use “Human Imitation of Huia,” Catalog #16209, William V. Ward, recordist, and to Collections Management Leader, Matthew Young, for technical help with editing.

Dr. Martin Fellows Hatch, Cornell Emeritus Professor, Musicology, Cornell University, for his “Transcription of Whistled Version of Huia Songs,” and to Dr. Christopher J. Miller, Senior Lecturer/Performer, Cornell University for transcription programming assistance.

Robert MacFarlane, of The Guardian, for spreading the echo.

Julianne Warren is author of Aldo Leopold’s Odyssey, an intellectual biography tracing the historical development of Leopold’s land health concept. Her other writings and presentations explore human orientations within Earth’s community of communities to discover what may be mutually life-enhancing. Presently, Julianne is working on an interdisciplinary environmental studies text. This narrative raises questions about the emergence of the Anthropocene, movements of human responsibility, and hope for new generations of young people. Her other work-in-progress is a triptych of volumes exploring Earth’s generativity. In these she contemplates ruins through the song of an extinct bird; reconstructs historic utopian models to reflect ecological care; and, inspired by a thirty thousand year old flowering fruit, interrogates evolutionary and cultural strategies for beginning, and beginning again. For five years, Julianne taught at New York University where she won a 2013 Martin Luther King, Jr. Faculty Award for her work with students in the climate justice movement. She hold a Ph.D. in wildlife ecology and conservation biology from the University of Illinois-Urbana-Champaign. Julianne currently serves as a Fellow with the Center for Humans and Nature.

Julianne Warren is author of Aldo Leopold’s Odyssey, an intellectual biography tracing the historical development of Leopold’s land health concept. Her other writings and presentations explore human orientations within Earth’s community of communities to discover what may be mutually life-enhancing. Presently, Julianne is working on an interdisciplinary environmental studies text. This narrative raises questions about the emergence of the Anthropocene, movements of human responsibility, and hope for new generations of young people. Her other work-in-progress is a triptych of volumes exploring Earth’s generativity. In these she contemplates ruins through the song of an extinct bird; reconstructs historic utopian models to reflect ecological care; and, inspired by a thirty thousand year old flowering fruit, interrogates evolutionary and cultural strategies for beginning, and beginning again. For five years, Julianne taught at New York University where she won a 2013 Martin Luther King, Jr. Faculty Award for her work with students in the climate justice movement. She hold a Ph.D. in wildlife ecology and conservation biology from the University of Illinois-Urbana-Champaign. Julianne currently serves as a Fellow with the Center for Humans and Nature.

[…] of the huia’s call. Warren’s exhibit makes Bateley’s crackly recording available. It is, as Warren puts it, “a soundtrack of the sacred voices of extinct birds echoing in that of a dead man echoing out of […]