The Current of Convictions

Dear Friends,

I am wading once again into W.S. Merwin’s papers—the notes, letters, and drafts we have found in towering stacks all around his study, in attic boxes, and stashed on shelves in his library. On several occasions, hours I’d set aside for organizing and inventorying have become afternoons, evenings, entire nights spent riding confluent currents of writing, contemplation, gardening, and activism.

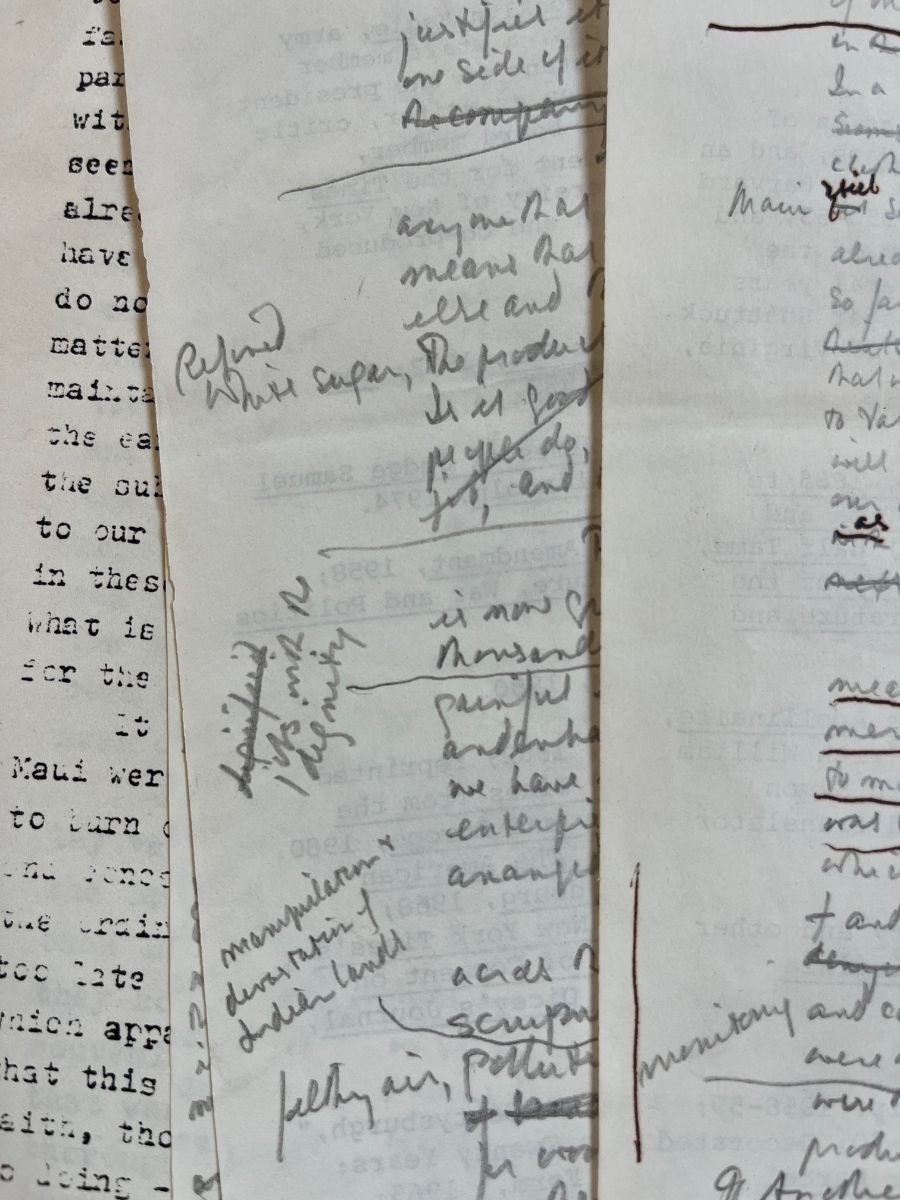

Poring over the remnants of a life fully and integrally lived, there is much to sustain one’s attention. There are of course artifacts of intimate encounters with language—a brittle old envelope, postmarked May 1984, pulled apart at the seams and flattened into scratch paper for an exercise in translation alongside a poem finding its course. And, there is a lot to overwhelm one’s attention: on the back sides of recycled correspondence and even junk mail, William scrawled a lengthy draft of a manuscript in a hand one must strain to make out. To guide my way through this wonder and overwhelm, I’ve learned to bring along a question. This month, as Maui commemorated last year’s devastating fires and looked squarely at the destructive dynamics they have further exposed, I carried this one: how did William, across the years, enact his sense of belonging to the island he had made his home?

Glimpses of answers (and many new questions) abound in box after densely packed box of the research materials that William began to gather in the late 1970s and early 1980s, soon after his arrival on Maui. In these, the contours of his curiosity and compassion for this island reveal themselves. I have written previously about the trove of research material we found in the attic on endangered species of the palm genus native to Hawaiʻi. We also found similar and extensive caches of material related to community efforts to “Save the ‘Ōhia Forests” and to end the use of the herbicide paraquat, along with “Bird Hazard Analyses” focused on the “Pacific Golden Plover (Pluvialis fulva) on Hawaiʻi’s Airfields.” There are hundreds of yellowing newspaper articles, position papers, and calls to action in support of anti-nuclear efforts on Hawaiʻi island and Maui, and extensive oral histories related to the sacred island of Kahoʻolawe, alongside photos and a journal recording William’s visit to that island to help plant trees after decades of bombing by the U.S. government.

Through the filter of these reams of William’s research comes the current of his convictions, and his voice, in a different key—a citizen’s voice, offered in articles and letters to the editor published locally and nationally, and through oral and written public testimony on a range of issues here in Hawaiʻi. In 1985, he published “Hawaii Wakes up to Pesticides” in The Nation. A year later, he offered a persuasive and elegant “Response to the Panel on Coal Burning in Hawaiʻi,” speaking not as “an expert of any kind,” but as “an ordinary citizen, and a resident of Maui.” Soon after, he published an essay in a Hawaiʻi newspaper amplifying the eye-opening findings of the seminal 1985 book Land and Power in Hawaiʻi. And in 1984, just after the four islands of Maui County adopted a nuclear-free ordinance, William wrote a letter to the editor of the Rengal Belau, the newspaper in print in Palau at that time:

I am writing to remind you that many people around the world, and many in the U.S. as well, have been following with admiration your courageous assertion of your self-respect in confronting those pressures, and to say that you have been and you are a source of inspiration and hope for many times your own population. We look forward to the Nuclear Free and Independent Pacific conference with that hope in mind, and encourage you in your defense of your own culture, your own dignity, and your own independence from all those who are arrogant and indifferent to who you are.

Among these papers, there are several essays and drafts that never found a public ear. Some words remain locked in a script that asks for several more evenings and nights to decipher. Others, undoubtedly, remained unpublished by choice, as William began in earnest to turn his hands toward his garden to enact his concerns for his island home, and for the world. To me, these oft-quoted words best capture this intentional shift in the allocation of his energy and attention:

In gardening, as my wife and I go about it here, what are called concerns—for ecology and the environment, for example—merge inevitably with work done every day, within sight of the house, with our own hands, and the concerns remain intimate and familiar rather than far away. They do not have to be thought about, they are at home in the mind. I have never lived anywhere that was more true.

Yesterday evening, as I was writing this note, I found among all of this material a letter to William from someone on Oʻahu, thanking him for “piercing the smokescreen, discerning the truth and proclaiming it for the rest of us.” This feels to me a heavy compliment to bear, and one I don’t think William would have felt comfortable accepting. And yet it is one I myself would offer to so many here on Maui, and in the world, who are putting their convictions into action, and confronting what needs to change. I am reminded of the many scales on which we might express our care for the world—by way of seed, syllable, or system—as each of us, in our own way, holds our concerns at home in the mind.

With gratitude for your friendship and support,

Sonnet