People and Place in Stories of Old

This post is from a series called Peʻahi Stories, a place- based literacy project launched in 2022.

While conducting research into the history of the ahupua‘a of Pe‘ahi and the moku of Hāmākualoa (where The Merwin Conservancy is located), cultural ethnographers Kepā and Onaona Maly drew on first-hand accounts and primary source documents to create a rich repository of information and stories. In our recent and first gathering with neighbors in the Merwins’ carport, over coffee and pastries from Komoda’s Bakery, we drew on some of this rich material to share voices from the past with those who live nearby. We also listened, as our neighbors–and now friends–shared stories that were new to us. This is the beauty of the Pe‘ahi Stories series: it allows us to contribute to the collective understanding of our home place.

Through the Malys’ research and through this journal series, we piece facets of history together to gain a better understanding of the relationship shared between Pe‘ahi, the regional environment, and the people of the land.

The Merwin Conservancy, protected in perpetuity through a conservation easement held by Hawai‘i Land Trust, is situated in the valley of Pe‘ahi, tucked between the slopes that rise up along either side of a dry stream bed. This stream valley and archaeological sites within it indicate that prior to the plantation era, traditional forms of agriculture were practiced here. Pe‘ahi Stream was very likely the water source that irrigated the lo‘i kalo (taro patches). Subsequent plantation era cultivation of pineapple erased any other recognizable archaeological features.

Handy, Handy and Pukui, in their book Native planters in old Hawaii : their life, lore, and environment (1972), provide us with first-hand accounts of native customs, practices, and traditions associated with lands of the Hāmākua region as they learned them from native residents during field visits in the 1930s-1950s. Their description follows:

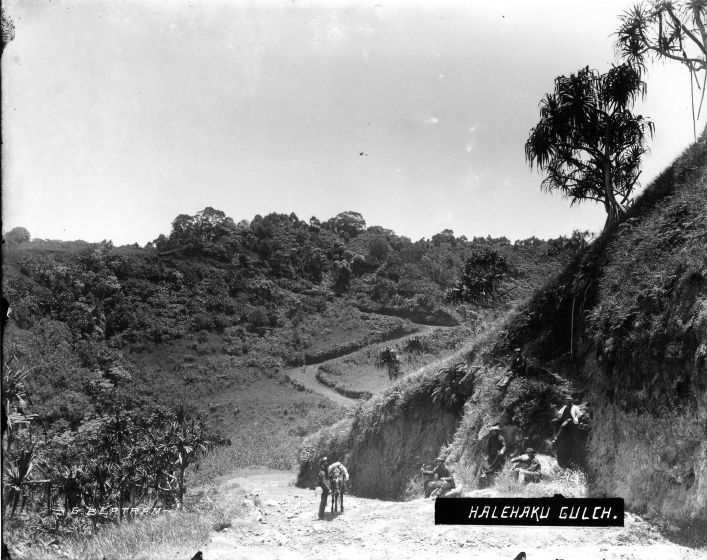

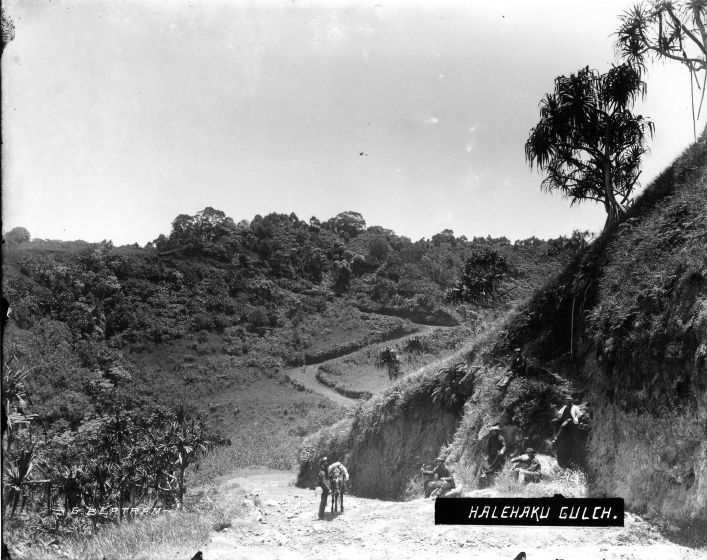

“Hamakua Poko (Short Hamakua) and Hamakua Loa (Long Hamakua) are two coastal regions where gently sloping kula lands intersected by small gulches come down to the sea along the northern coast line (sic) of East Maui. Maliko Stream, flowing in a gulch that widens and has a flat bottom to seaward, in pre-sugar-plantation days had a considerable number of lo‘i. East of Maliko the number of named ahupua‘a is evidence of habitation along this coast. Kuiaha Gulch, beyond Maliko, has a good stream and there were probably a few lo‘i. Two kama‘aina at Ke‘anae said that there were small lo‘i developments watered by Ho‘olawa, Waipi‘o, Hanehoi, Hoalua, Kailua, and Na‘ili‘ilihaele Streams, all of which flow in deep gulches. Stream taro was probably planted along the watercourses well up into the higher kula land and forest taro throughout the lower forest zone. The number of very narrow ahupua’a thus utilized along the whole of the Hamakua coast indicates that there must have been a very considerable population.This would be despite the fact that it is an area of only moderate precipitation because of being too low to draw rain out of trade winds flowing down the coast from the rugged and wet northeast Ko‘olau area that lies beyond. It was probably a favorable region for breadfruit, banana, sugar cane, arrowroot; and for yams and ‘awa in the interior. The slopes between gulches were covered with good soil, excellent for sweet-potato planting. The low coast is indented by a number of small bays offering good opportunity for fishing. The Alaloa, or “Long-road,” that went around Maui passed through Hamakua close to the shore, crossing streams where the gulches opened to the sea.”

There are a number of poetic references to rains and winds across the Hāmākualoa area. One notable rain is called “Ka ua pe‘epe‘e hala o Hāmākua” (The rain that causes one to hide/seek shelter under the pandnus of Hāmākua). This was found in Nupepa Ka Lahui Hawaii, Dekemaba 9, 1875:3. The reference is found in a lamentation for Kilioe, a native woman (86 years) of Kea’a’ula, whose descendant, Poohina, resided at Pe‘ahi.

In a later lamentation for Sarai Namai Kaleialoha, the composer speaks of Pe‘ahi and the rain that causes one to hide in the shelter of the hala trees:

Kepakemaba 19, 1919 (aoao 8)

Nupepa Kuokoa

Kuu Lei Makamae He Wahine Ua Hala. (Kuu wahine, Mrs. Sarai Namai Kaleialoha)…E na pali hauliuli na kahawai o ka uka o Peahi, ka ua peepee puhala o Hamakua e ua au ko olua hoopulu ana i kona ili. E na lae kahakai Koale, Puniawa, Eleile me Maliko e, ua pau ko oukou hoope ana i na hunakai i kona ili. E Pauwela me kou mau kahawai e, ua pau ka hehi ana a kaahele a maluna o kou leo aloha. Ua hala, ua nalo, ua kuu kaluhi o kuu leimomi makamae…

Owau iho no me ka luuluu,

Dan Kaleialoha. Pauwela, Maui, Sept. 13, 1919.…O ye green cliffs of the valley in the uplands of Pe‘ahi, where the rainfall causes one to hide under the pandanus trees, the rains which moistened your skin. O ocean points of Koale, Puniawa, Eleile and Maliko, you shall not again moisten her skin with the sea spray. O Pauwela with your many streams, her beloved voice shall never again travel across you. She has passed on, she is lost, the burdens of my beloved pearl lei have been set aside…(165)

In earlier newspaper accounts, we hear from visitors to Pe‘ahi, who shared detailed descriptions of their time spent here, and offered their appreciation for a warm welcome, a generous feast, and “drink that uplifts oneʻs eyelashes:”

Augate 2, 1918 (aoao 8)

Nupepa Kuokoa

He Hoomaikai“In Appreciation… Will you please make known my appreciation to all of the people who welcomed us at Peahi, Maui. While I was yet a stranger upon arriving at that place, at the invitation of Helekaha Makua, we were fed and had more than enough to drink. Everything that day was perfect. There was an abundance of food, fat pig, limpets gathered from the cliff-base, mahikihiki shrimp of Huelo and pohole fern shoots, and drink that uplifts one’s eyelashes. We are full of appreciation to the fine gentleman, Kaui, for whom no fault was witnessed from our arrival to our departure… Mrs. Nohohui Kapuaa.” (157)

In a later account, we learn about what that special drink might have been:

Novemaba 7, 1860 (aoao 133)

Ka Hae Hawaii

Auwe! Auwe! He Inu Uwala!…Here at Halehaku, Honopou, and Holawa, Hamakualoa, men women and children are drinking sweet potato, mountain apple, and molasses vinegar, made as intoxicants by the brethren, which they have called “kukaemanu” (bird droppings).

If they hear, “there at Holawa is the kukaemanu,” at the place of Keoho, Opunui, or Kawaa, then men and women go there. (145)

It warms my heart to hear these accounts of the winds, the rains, the lively gatherings, and of how residents of the past shared their love of this place with each other in person and through oral and written language. These deep connections to the land–all of the ways it can feed us physically, spiritually, emotionally– live on in the many who are caring for these places today.

We are grateful to continue talking story with our neighbors and friends at The Merwin Conservancy, sharing stories of old together. We look forward to gathering again to share a meal and raise our mugs of tea and coffee, enriching our connections to our home places in Hāmākualoa. And we look forward to sharing more of what we learn through Pe‘ahi Stories.

This program is made possible in part by funding from Hawaiʻi Council of the Humanities through the Sustaining the Humanities through the American Rescue Plan (SHARP) with funds from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) and the federal American Rescue Plan (ARP) Act.

Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this series, do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.