A Library Is Alive

It’s an image that calls itself up randomly sometimes: the corner of the garden. It’s literally a corner—two fences that meet at a right angle, barely containing an explosion of fronds and ferns. The moment I see it from the street, I unplug from this world. Soon, I’ll be in one without cellular service or the internet, hidden by a shady valley in a small house that holds an enormous collection of books.

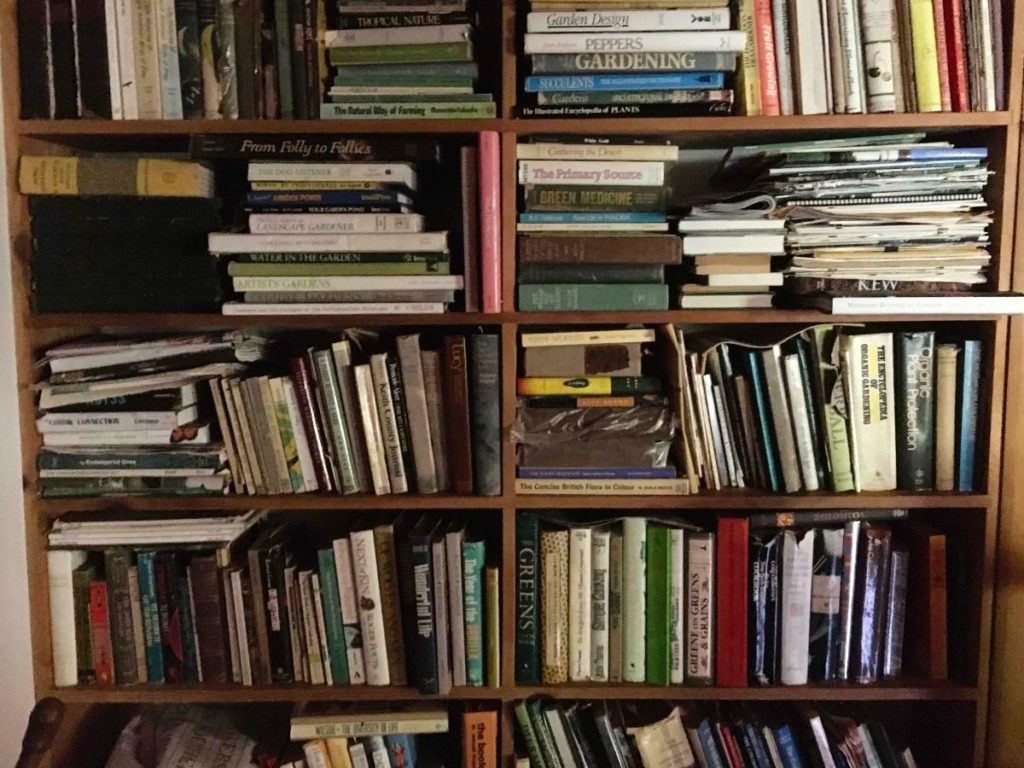

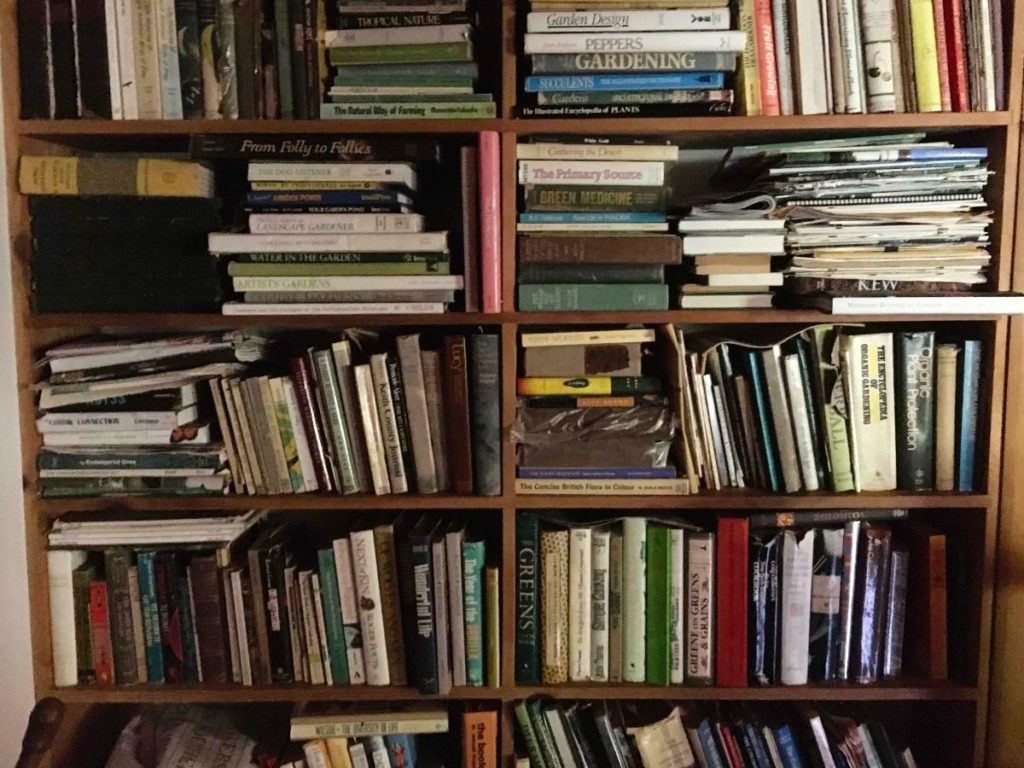

Picture dusty floor to ceiling shelves bowing under the haphazard weight of not just literature and poetry, but works on ecology, gardening, Buddhism, Hawaiiana, cooking. I often find myself thinking of W.S. and Paula Merwin’s library as its own sort of seed bank. As in: if the world as we know it ends, at least there will be this repository of wisdom. I think of it as not unlike the great libraries of the ancient world that ushered important works through the dark ages.

A private collection this ungainly and diverse would be remarkable in any city of the world. That it exists in this obscure nook on a remote island in the middle of the Pacific feels, to me, miraculous, a treasure to be guarded, preserved, and someday, conscientiously, shared. All personal libraries are intimate curations that invite conjecture, but this one seems more galaxy than mirror. It’s a forest and the luxury of getting lost here is the essential opposite of, say, browsing the staff picks at a chain bookstore, though even that is starting to seem quaint in the face of the algorithm.

In the house, all of the clocks are set to a different hour, not intentionally, and I hope they remain that way as it creates a sense that time isn’t passing as much as it is being metabolized; instead of a grumpy taskmaster, it’s just another nutrient. There is a transparency to it, as if it has very little to do with the actual day. I call this “library time,” which, not unlike “garden time,” is marked by increments of growth and decay.

Some of the books fall apart in our careful, gloved hands. Others, though older than our combined ages, look like they came off the presses last week. We clean and catalogue each volume, from 19th century botanical treatises to obscure French novels perhaps purchased one afternoon while walking along the Seine. Between their pages, we discover dried flowers, photographs, grocery lists, notes, scraps of poems. Each book is the site of two stories, the one told in its pages, and a personal one, the journey it took as an object that somehow ended here, in this jungle home.

These artifacts from a life so fully lived require gentle and thorough care. A rare combination. It would be easy to feel a sense of urgency at the sheer scope, the almost absurd abundance, of this collection that must be gone through, book by book, but one can’t be gentle and thorough when rushing. A first edition dust jacket is so easily torn, a forgotten letter, tucked between pages, easily overlooked. And so I try not to think too much about the future, focusing instead on whatever small world I hold in my hand.

We are grateful to Arlynna Livingston, Janie Davis, Lydia Shigekane, Pauline Sheldon, Karen Sullivan, and Jana Wolff for the support that made this preliminary phase of library cataloguing possible.

About the author:

Andrea Perkins served as The Merwin Conservancy’s programs and development coordinator. Her background is in journalism and poetry and her writing has appeared in various publications, often under an alias. The child of librarians, she grew up amid the stacks. During her undergraduate years, she worked with rare books at University of Utah’s Marriott Library.