Uprooting and Renewal

“Director’s Notes” are excerpts from our monthly email newsletter, “Stories from the Garden.” Subscribe and see past issues here.

Dear Friends,

In the early and windy weeks of February, one of the last remaining ironwoods that W.S. Merwin planted in his first days here in Peʻahi uprooted and fell. Fifty feet downslope, it caught an impossibly tall avocado tree, which in turn gave way. A milo, too, broke at its trunk and tumbled. Beneath the extensive debris—a knot of dragon fruit and invasive vines, which had crawled all the way to the tips of that towering ironwood— lay about a dozen crushed palms.

It will not surprise longtime readers of these Stories from the Garden that in the days following this tumult, I turned to an essay I revisit often. William wrote “The House and Garden: The Emergence of a Dream” in 2010, the very year in which the Conservancy was founded. The essay begins with his arrival here in the late 1970s, and his dream “of having a chance, one day, to try to restore a bit of the earth’s surface that had been abused by human ‘improvement.’ ” It ends with the hope that “a Conservancy will want and will be able to save this bit of the Peʻahi streambed—what we have made here for those who come after us.” And in between, the essay recounts William’s early gestures toward the land in a way that reveals a set of clear convictions. He recalls choosing the site of his future house not up along the ridge near the road, but instead halfway down the valley slope—this to favor presence and attention, a sense of discovery and arrival, over any efficiency afforded by convenience; “the idol of the world of terminal acceleration,” he wrote, “had never been my guide.” William writes of planting around his newly built home such that one day the house itself would appear “to have grown out of the surroundings without intruding upon them.” Through all of William’s recollections runs a commitment to “disturb the land as little as possible,” “to live as someone who belonged here,” and to relate to the land with a sense of time that reaches far beyond a human life. Out of this essay’s rich soil grows the story of the ironwoods:

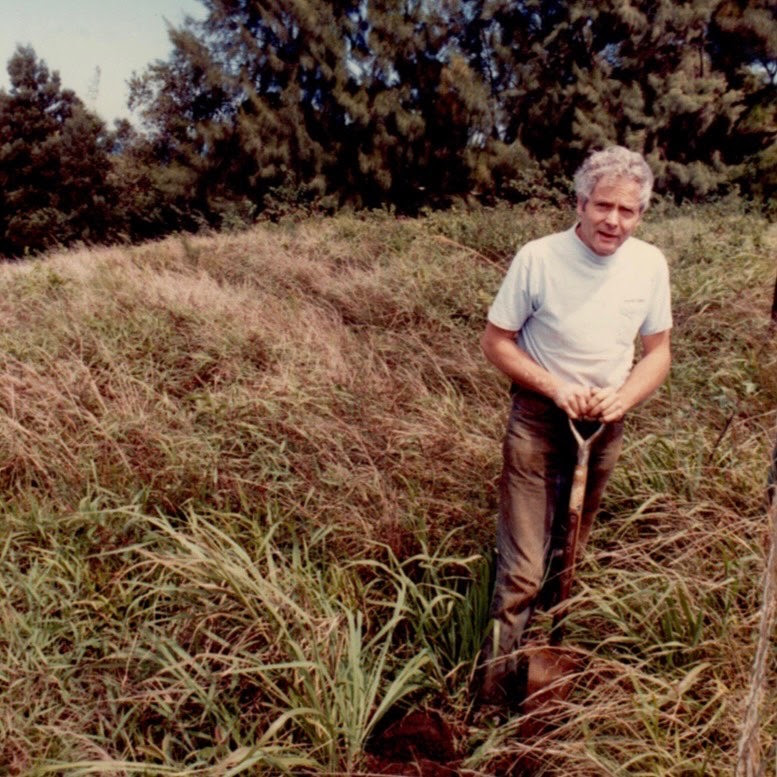

Although I began with a naïve aspiration to restore a few acres of pure Hawaiian rainforest, the first trees I planted here were not indigenous to Hawaii. No native trees would grow in the parched, wind-swept conditions and the leached-out soil, as they were then, up along the ridge. I planted Casuarinas, known locally as “ironwoods,” beautiful trees that look like tall, weeping pines, and were named, by the seventeenth-century botanist Rumphius for the Cassowary bird with its long, graceful wings. But the whole genus has acquired a bad name in Hawaii because the first species planted here was aggressively invasive, sending up outriders from its running surface roots. I was careful to plant species that had no such intrusive habits and were especially graceful. Even in the conditions here they grew rapidly, and within a few years they began to form a miniclimate, as they shaded the ground, added humus with their fallen needles, held the water after heavy rains, and put nitrogen back into the soil…They broke the wind with a lovely sound, the long limbs swaying…Now they are being replaced, in the habitat they improved, by young palms.

As I emerge from my reading this time, and turn back to the tumult in the garden, the nature of the transition upon us is quite plain. The ironwoods, the first trees planted here, have completed their work in the garden, as has William; the vitality that together they set in motion here is now ours to tend, through disruption and renewal, and around again. We have entered the cycle of life that began well before our arrival (and even before William’s) and will continue well beyond our lives. Along the way, we carry forward this set of clear convictions, even as we express them in our own way, in the contemporary context of a rapidly changing world. For now, as a friend of the Conservancy wrote in recent days of the ironwood’s fall, we have front row seats to the slow and wondrous process of ecological succession, here in this garden that speaks to the world.

Wishing you well in these times of change, and always,

Sonnet